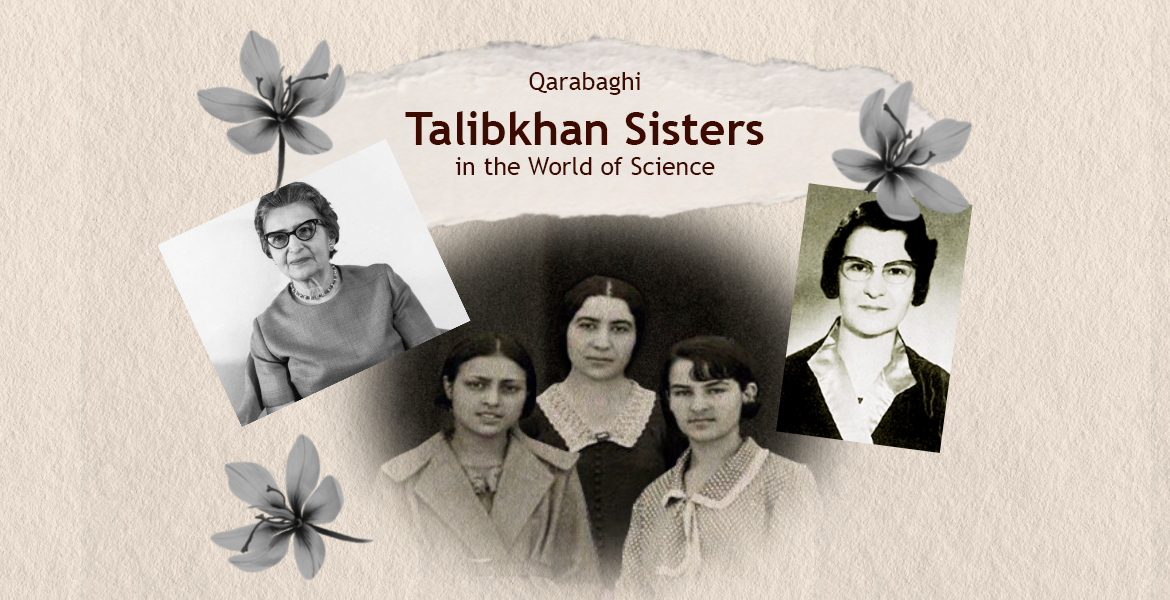

Renowned Scientist Sisters from Karabakh

Surayya, Gamar, and Dilshad were born in Shusha, Azerbaijan, at the turn of the 20th century. They also had a brother, Hussein. Their father, Talibkhan Bey Talibkhanov, was a descendant of the Karabakh khans and served as a district police chief both during the Tsarist rule in Russia and after Azerbaijan gained independence as the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Their mother’s name was Kheyrannisa.

When the Soviets seized power, the family no longer felt safe in Azerbaijan. The sisters’ uncle, Hussein Yanar Mirzajamalov—known as “Uncle” to many in Azerbaijan and a close friend of Mammad Emin Rasulzade and Yusif Vezir Chemenzeminli—helped the family relocate to Turkey. Hussein Bey, a teacher, translator, and activist, was one of the first prominent members of the Azerbaijani immigrant community. Although he had no children of his own, he devoted his love and care to his sister Kheyrannisa’s children.

His dedication bore fruit, as all three sisters became notable scientists and cultural figures of their time. All four siblings spoke Turkish, Russian, and English, with Gamar and Dilshad also fluent in German.

Surayya Talibkhanbeyli (1899-1974)

The eldest of the sisters, Surayya, became a well-known philologist and folklorist, publishing articles on the Azerbaijani language. After graduating from the Languages and Literature faculty of Istanbul University, she married Mustafa Vekilli (1896-1965), a political refugee and former Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic’s government. (His name appeared in criminal investigation files related to his cousin, Madina Giyasbeyli-Vekilova, a lecturer and respected figure who was arrested in Baku and sentenced to death for her affiliation with the Musavat party.)

Following their divorce, Surayya resumed her scientific career, publishing comparative studies of Azerbaijani and Anatolian dialects. She received great support from her compatriot Ahmed Jafaroglu (1899-1976), an associate professor at Istanbul University and one of the foremost Turkologists. In the 1930s, Ahmed Bey edited *Azerbaijan Yurd Bilgisi*, a magazine in which Surayya’s articles on “Comparison of Karabakh and Istanbul Dialects” were featured across four issues. Later, Surayya married Anatolian Turk Behid Odoglu, with whom she had four children: Berin, Murad, Jan, and Tarik. She taught literature in Istanbul lyceums for many years until her death.

Dilshad Talibkhan Elbrus (1915-1979)

Dilshad became Azerbaijan’s first female nuclear physicist. After attending the Istanbul Girls’ Lyceum, she earned her university degree in Physics and Chemistry in 1934, starting her scientific career as an assistant at the Institute of Experimental Physics. By 1961, she was a professor at Ege University in Izmir, Turkey, and was recognized as Turkey’s first female researcher in nuclear physics. She authored two books and numerous articles in her field. Dilshad actively participated in events held by Azerbaijani political immigrants led by M.A. Rasulzade, which were covered by the Azerbaijani immigrant press.

Besides her achievements in science, Dilshad khanum was an accomplished pianist, often performing Azerbaijani music. She also cared for her sister Surayya’s son. Upon her death, Turkey mourned her passing as a great physicist, yet her contributions remained unknown in Azerbaijan.

Gamar (Talibkhanbeyli) Agaoglu (1903-1984)

The youngest sister, Gamar, was only 18 when the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic fell. She likely met her future husband, Muhammed Agayev (later known as Mehmet Agaoglu), in Baku. The young couple emigrated, married, and initially lived in Germany before settling in Austria. Gamar earned her Doctorate in Oriental History from Istanbul University in 1927. When her husband received an offer to work at the Detroit Art Institute, the family moved permanently to the U.S.

Mehmet Agaogly became a renowned lecturer and Fellow in Oriental Art Studies, establishing the first Department of Islamic Art History in the U.S. in 1933. They lived in a modest American apartment, frequently hosting Azerbaijani and Turkish youths who gathered to enjoy music and discuss the past. Yet, Gamar had aspirations beyond domestic life.

After completing postgraduate studies at the University of Michigan in 1938, she joined the Museum of Anthropology as a researcher. Her work was interrupted by WWII when she was asked to teach Russian to U.S. military officers for two years. After the war, she returned to the museum, where she became the only female curator and served until 1974. The museum’s website notes, “Gamar singlehandedly reformed the study of Asian ceramics.” She also taught as a professor at her alma mater.

Gamar khanum specialized in Southeast Asian ceramics, conducting groundbreaking research and handling archaeological finds. She authored over 40 publications and several books, which remain accessible online. She traveled widely, contributing significantly to studies on cultural heritage.

Although both she and Mehmet Agaogly became successful in their fields, their marriage ultimately ended. Mehmet’s second wife, Dorotha, donated his art collection to the Freer Gallery of Art. In 1959, Gamar khanum followed suit, donating his manuscripts and unfinished works to the gallery. Their daughter, Gultekin (known as Gilly), followed in her parents’ footsteps, building a career in art. After Gamar’s death, Gultekin donated her mother’s invaluable books and materials to the Museum of Anthropology. Gultekin passed away in August 2018 in Ohio.