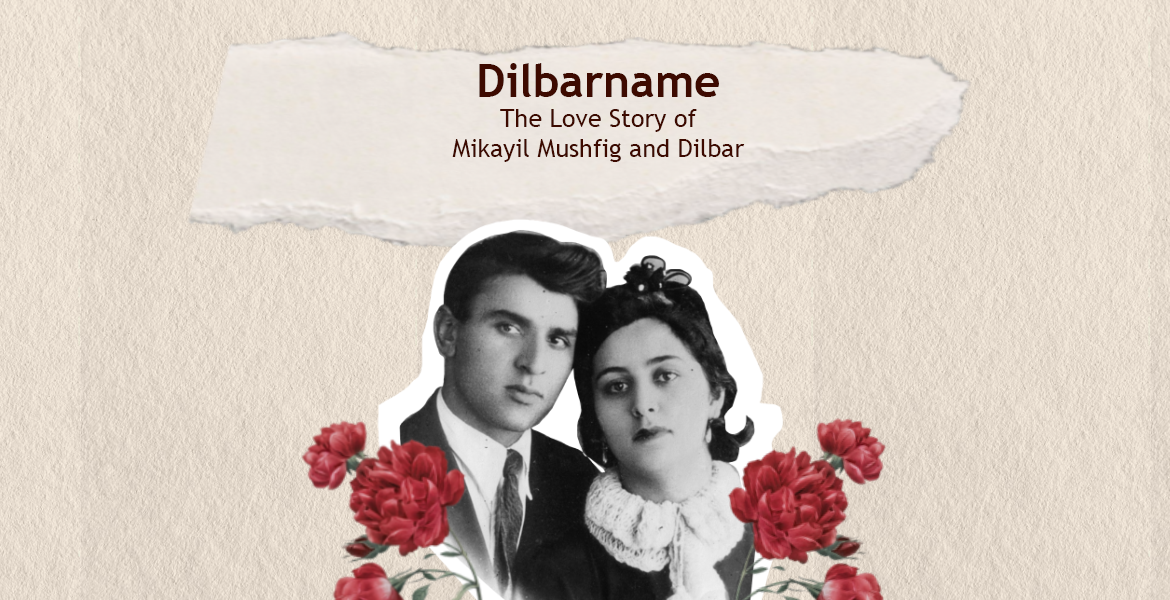

Dilbarname: The Love Story of Mikayil Mushfig and Dilbar

Their whole history is a continuous chain of accidents. Dilbar’s uncle, Idris Akhundzade, taught literature, counting Huseyn Javid and Ahmad Javad among his closest friends. Once, visiting his brother in Ganja, he saw his niece’s difficult life with her stepmother. Without hesitation, he took her with him to Baku. Who knows if Dilbar and Mushfig would have met had this not happened?

One day, Dilbar’s uncle’s wife took her to her graduation party. The event hadn’t started yet; visitors crowded in the lobby, and suddenly, a young, handsome, and talented fellow student, eager to announce himself to the world, approached her.

“Dilbar, let me introduce Mikayil Mushfig to you.”

She’d heard of him before; after all, he was one of her uncle’s close friends, who often spoke of Mikayil. But this was her first time seeing him. Whether by fate or accident, he sat behind her. Her long, thick braids seemed to be Cupid’s arrows: she tossed her hair back, and it brushed his face—the poet’s heart surrendered right there without a fight. For each meeting, he brought her a “gift”—at her request.

– Please, I beg you, let’s meet more often.

– Only on one condition.

– I’ll do anything, just tell me.

– For each meeting, you’ll compose a new poem.

From Dilbar Akhundzade’s memoirs, “My Days with Mushfig.”

He devoted to her his best poems, spoke to her in verses, sent her letters filled with dedication, and she inspired him to create delicate love lyrics. Once, he even told her:

Oh, Dilbar, you see, you’ve captivated me! I fear they’ll say, ‘Mushfig has turned lyricist.’

Remember, my sweet, someday, demise

Love sparks reflected in my eyes

From the moment your hair inspired me

A thin veil of fog enveloped me

And no hills, nor plains I could see.

Mikayil Mushfig

(Translation by M. Rasulzade)

He sought every chance to meet her, waited for her, and expressed his feelings in verses. She made him wait anxiously until she whispered her precious “yes”—but again, on one condition.

Her mother always wanted one thing: for her daughter to get an education at all costs, to be independent. Having experienced unhappiness herself, she wished to protect Dilbar. Because of this, Dilbar delayed their wedding. Mushfig, understanding, supported her dreams. He often addressed themes that today we call “women’s empowerment.”

Their long engagement was captured in verses; separations, lovesickness, and long-awaited meetings only strengthened their love, growing with each passing day. Their engagement and wedding became events of the century. Sadly, no photographs remain, but the grandiosity could be seen in the guest list: Huseyn Javid, Abdulla Shaig, Ahmed Javad, Bulbul, Samed Vurgun, Mir Jalal, Rasul Rza, and many others. It was more than a wedding—it was a genuine celebration of beauty, love, music, and, of course, poetry.

Their home was always full of visitors: great poets, writers, even homeless children whom Mushfig often brought home, feeding and clothing them, and helping place them in orphanages. Dilbar graduated from medical school, became an activist, and even served on the Baku Soviet Council.

A year later, joy visited them again with the birth of their son, Yalchin, though he would bring grief by passing away before his first birthday.

“Since our marriage, I’ve understood the mastery needed to craft words, and what a poet’s life entails. Only now do I realize the effort Mushfig put into achieving the fluidity and melody of verse, struggling over each word to create new lines.” He once said:

“The unhappiest moments of my life are those spent without poetry.”

Many couples, fearing looming threats, filed for divorce to protect wives and children. Some even renounced each other. But Dilbar never considered such a thing. First, Mushfig was detained; then they came for her. The interrogations continued, tortures never ceased. She never renounced him, protecting his name until the end. They cut her hair in prison—a poetic symbol of their love. She was tortured more than others, told to sign papers declaring him guilty. Her answer was always, “no.”

“Ah, Mushfig, if only we could reclaim those days…”

The tortures took a toll on her health. Her doctor noted she developed various ailments: heart issues, kidney problems, nervous disorders, diabetes… Unable to break her spirit, they declared her insane and transferred her from the prison hospital to a psychiatric ward. Recognizing her, doctors released her with a clean bill of health. She returned to Ganja to her mother’s house, where she spent years recovering. Initially, she could not speak, understand, or even remember who she or Mushfig was. Doctors advised her to start a new life, even to start a new family. She was young, carrying this burden on fragile shoulders—with no husband, no children, no reason to wake up in the morning…

“For the whole night, I didn’t sleep. Dilbar was out of her mind, stamping around, shouting confusedly. She pleaded, “Let Mushfig come… call my father… I’ll die for my beloved. They think I’ve gone mad. Oh, Allah, they tell me You don’t exist, please have mercy on me…” She spoke tenderly to Mushfig, as if he were beside her in the cell, before erupting in hysteria. Her state shattered what courage we had left; she was, after all, our Dilbar, the wife of our dear Mushfig.”

From her cellmate’s diary, February 27, 1938.

After prison, she bore the label “spouse of an enemy of the people,” which meant endless hardships. Many turned away, but there were some who stayed kind. She eventually remarried, obtained exoneration papers, and moved to Baku with her children. For a time, they even stayed with Mushfig’s relatives.

Dilbar lived for Mushfig’s memory, making speeches, writing letters, and recording her memories. At Mushfig’s 80th anniversary, though frail, she found strength to deliver a speech as if lifted by unseen forces.

After her suffering, she restored his lyrics. Though she went through unimaginable torment, she could finally pen her memoirs. We owe much to this woman for preserving Mushfig’s poetry.

When Mushfig was arrested, a large folder titled Dilbarname was left on his table, filled with his verses. It disappeared, but she pieced his works back together and even began writing poetry herself—though she never considered herself a poet.

Light of my eyes, my love

How shall I exist if thou art gone,

Daffodils, violets in thy garden are in bloom,

How shall I gather them if thou art gone?

Dilbar Akhundzade, “If Thou Art Gone”

(Translation by M. Rasulzade)

Many women claimed Mushfig dedicated verses to them. Dilbar would laugh, saying he could devote a poem to a woman he met, or one he dreamt about. Her name was immortalized in his verses, many of which were set to music and became songs.

Dilbar was capable and talented; she could have been a doctor, a teacher. But her health was severely impacted by the tragedy, limiting her abilities. She advised her children to seek education and a trade. The only gratitude she expressed to the Soviet Union was for granting women rights to work and get an education. Though she raised her children amid hardship, she felt fulfilled.

She spent her life haunted by fear, attempting to shed the shadows of her past, piecing together her husband’s legacy, and raising her children under trying conditions. But fate was kind enough to let her live to see her grandchildren. The first grandchild was named after her—Dilbar.

This story was written from the words of Leyla Akhundzade, daughter of Dilbar Khanum, the only love of the great Mikail Mushfig.